Culturally Relevant Teaching (CRT) is a popular topic for discussion and research, and it continues to gain more traction through practical application in classrooms worldwide. Certainly, as many teachers look around their classrooms, they recognize that demographics are changing, and student populations are becoming increasingly more diverse. It is more likely than ever that teachers will not look like or have the same cultural or linguistic background as many of their students.1 This means that some students will be entering classrooms with valuable learning strategies developed within their home communities, but these strategies may be very different from what their teachers are accustomed to using.

As mid-career Adventist educators, we (the authors of this article) have each experienced unique opportunities to be challenged, to reflect, and to continuously grow in our approaches to CRT. It has been both a journey of discovery and a reminder to approach CRT from a posture of humility. We have come to recognize the importance of owning our own cultural identities and acknowledging their impact on how we think, teach, and live.

We also value spiritual development and believe that the Adventist teacher has a unique calling and privilege to help students integrate their faith, learning, and life with rigor and perspective. As Adventist educators, we have an ethical responsibility to ensure that all students are provided with a redemptive education, one in which they are treated with dignity and respect while being encouraged to become “thinkers, not mere reflectors of other people’s thought.”2 Therefore, we must go beyond stereotypes and assumptions about ourselves and others to proceed with purposeful action. Culturally Relevant Teaching provides one avenue we can use to immerse ourselves in this work.

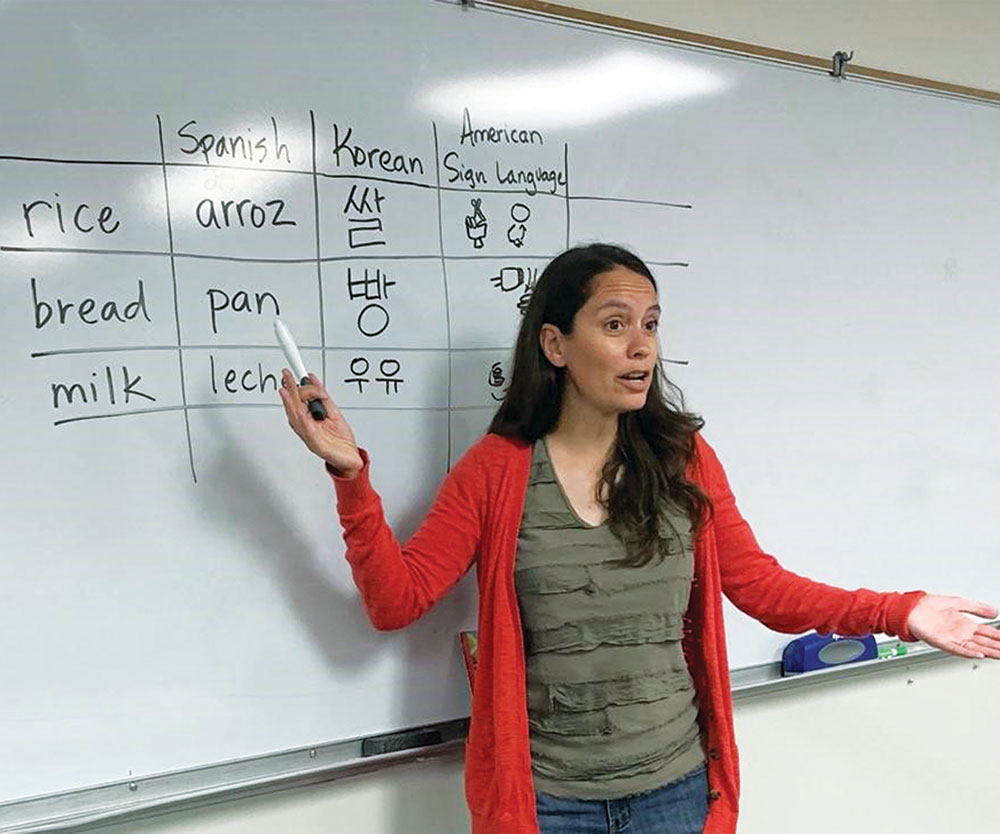

Charissa Boyd demonstrating multilingual language instruction.

While how this is implemented will look different around the globe, we will share our experiences as teachers who have worked in a wide range of educational settings in the United States and other countries. The tips provided in this article have been drawn from core concepts, implementation strategies, and lessons learned while in the field. Throughout the article we will include our own personal experiences as we discuss the tips. These tips are foundational to the successful implementation of CRT by Adventist educators, and emerge from three interrelated foundational components of culturally relevant teaching—setting, curriculum, and engagement.

What Is Culturally Relevant Teaching?

So, what is Culturally Relevant Teaching, exactly? CRT is a term coined by Gloria Ladson-Billings to describe “a pedagogy that empowers students intellectually, socially, emotionally, and politically by using cultural referents to impart knowledge, skills, and attitudes.”3 It was birthed out of Ladson-Billings’ research to identify what made American public school teachers successful within low socio-economic, primarily African American school districts. Through her research, she identified three core criteria of CRT: Students must do the following: (1) experience academic success; (2) maintain or develop cultural competence; and (3) develop a critical consciousness through which they can challenge the status quo of the current social order.4

Tip 1. Consider the setting.

Globally, a growing number of classrooms contain students from diverse cultural backgrounds. Positioned within both school and community contexts, educators must ensure that this dual context is reflected in their work. They can do so by honoring the history and voice of communities represented in their classrooms through reinforcing their commitment to excellence and high expectations, and through integrating students’ home languages within the classroom.5 Since communities differ, it is the teacher’s responsibility to assess and evaluate his or her setting through careful observation, listening, dialogue, and reflection. And, since the setting will change with each new school year or semester, this type of reflection must be ongoing.

Tip 2. Make peace with your own identity.

In order to understand and identify with others, a teacher needs to understand himself or herself. We (the authors) each committed to exploring our individual identities, knowing that we would be teaching students whose experiences differed from our own. A primary way that we have done this work is to come to terms with our own racial and ethnic identities (see Sidebar 1). Once a teacher has committed to self-reflection and identity work, he or she is well-positioned to incorporate the other elements of CRT.

Tip 3. Embrace and maintain high expectations for both academics and behavior.

I (CG) start each school year having high expectations of my students. It is maintaining those expectations throughout the year that often poses a challenge. In order to maintain this as a priority, I’ve found a few practices helpful:

- First, establish a connection between the commitment to excellence within the local cultural and community history and the high expectations being set for students.

- Second, keep expectations visible. Designate a prominent space in your classroom where you display curriculum standards that apply to the content being taught. The behavior code of conduct should also be visible. One way to do this is to laminate a large version of your classroom code of conduct (written in student-friendly language), and have all students sign it. Display it along with motivational quotes.

- Third, be consistent. Use rubrics to evaluate assignments so that all student work is assessed using the same criteria. This will mean teaching for mastery while providing instructional scaffolding for those who need it. For behavior codes of conduct, hold students (and yourself!) accountable when the code of conduct is broken.

Research tells us that teacher expectations have a significant influence on student performance, both positively and negatively.6 Seventh-day Adventist educators have a unique opportunity to live out the foundational biblical belief that all people are created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27), and that “Every human being, created in the image of God, is endowed with a power akin to that of the Creator—individuality, power to think and to do.”7 In many public schools in the United States, students of color are overrepresented in special-education classrooms8 and underrepresented in advanced-placement classes and gifted-education programs.9 In contrast, many students in Adventist schools have limited access to such services, and therefore teachers and administrators must advocate for and support those students who need additional resources (special education, advanced placement, and gifted-education programs), keep the bar set high, and scaffold students’ learning for rigorous and successful goal attainment.

Tip 4. Embrace multilingualism.

In my personal experience, I (CB) quickly learned that one of the most powerful tools for creating a culturally relevant classroom environment is to integrate the native languages of my students into the studies in every way possible. Even the implementation of simple steps in this direction gave my students permission to show pride in their heritage and to be their whole selves, not just their “English-language selves,” in my classroom. Students who initially refused to speak at all started participating in classroom discussions when they realized that their voice/language was not going to be silenced.

There are multiple ways to incorporate your students’ native languages into day-to-day classroom activities:

- Multilingual word walls and bulletin boards.10

- Scaffolding tasks (allowing students to use their native languages for tasks like online research, note taking, first drafts of writing assignments, etc.).11

- Dual language and translation projects.12

- Language study (comparing vocabulary words in multiple languages or setting aside a week or a month for learning specific words and phrases in the native language of one or more of the students).13

These strategies can be used in classrooms containing several students who speak different languages, and even in classrooms that have only a few students. The language-rich environment that results from multilingual word walls, bulletin boards, or dual-language projects will benefit all learners, even native English speakers.14

Tip 5. Examine curriculum and learning materials for bias.

Examining the curriculum from a culturally relevant teaching perspective will help teachers engage students in critical thinking, encourage them to invest in intentional opportunities for every student to develop his or her voice, and empower all students to engage with education as a way to seek justice and reconciliation.

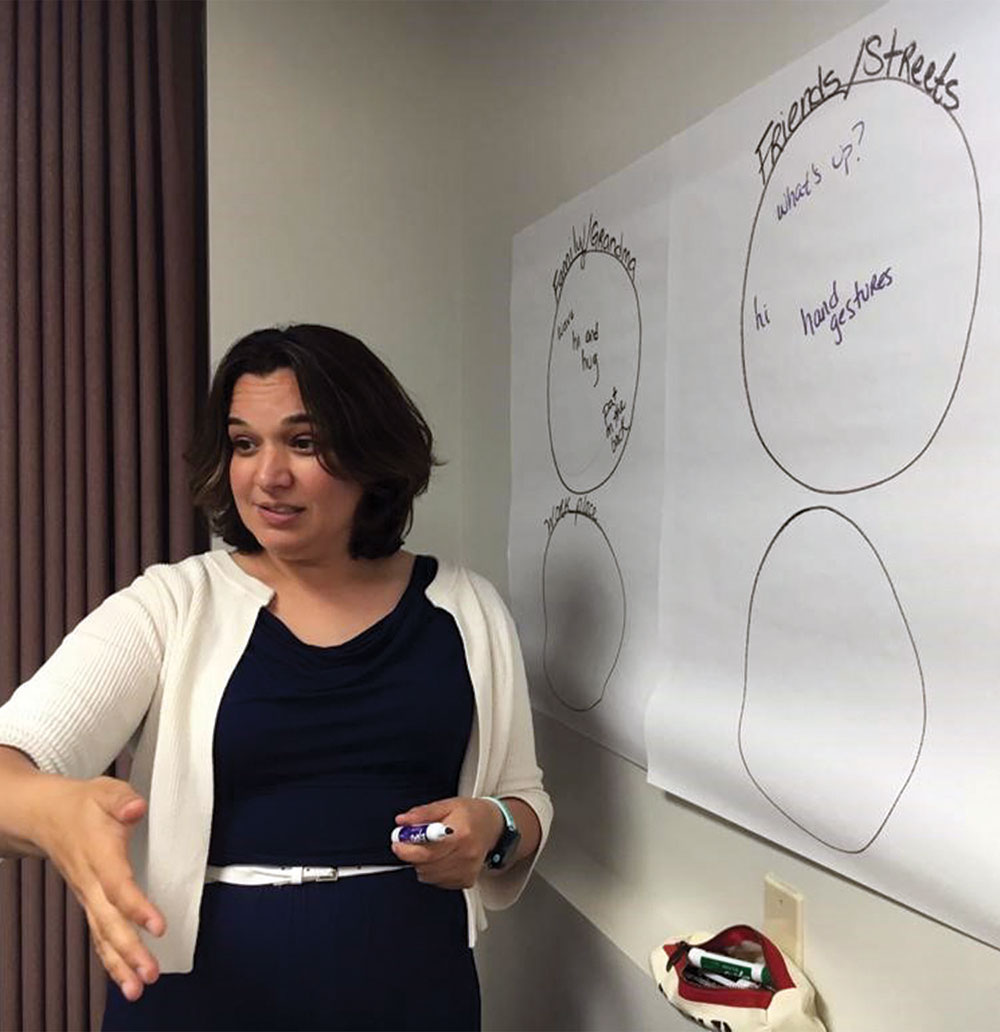

Charity Garcia demonstrating Circles of Interest to help students communicate in various social settings.

Textbooks or other provided learning materials used to teach in Adventist schools are often examined and approved by the union or division office and mandated for use. Even so, it is necessary for teachers to review the resources for bias or omitted perspectives. When teachers use these curriculum resources without taking the time to examine them for bias, they may miss valuable opportunities for students to engage in critical conversation and to experience empowerment. I (CG) made this mistake my first-year teaching World War II history to Navajo middle school students. I read aloud the textbook’s one paragraph on Navajo Code Talkers and spent less than five minutes on the topic. Subsequent student ambivalence clearly indicated that I had missed a valuable opportunity for these middle schoolers to feel empowered by their tribe’s pivotal role in the outcome of the war. I began to realize that Navajo Code Talkers were not just part of “Navajo history”; they were part of United States history. After learning this lesson, I adjusted future unit planning―not only for World War II but also when dealing with other concepts such as Manifest Destiny.

Tip 6. Seek out multiple perspectives.

Closely related to Tip No. 5, teachers should examine curriculum materials from multiple perspectives. Where he or she identifies bias in curriculum documents, it is the teacher’s responsibility to include other perspectives—particularly the ones that otherwise would not be part of the conversation. This is especially important when seeking to understand the community in which the school exists from a strengths-based perspective (identifying positive assets within a community such as people and resources) rather than from a deficit model (seeing only what the community lacks).15

I (CG) have found developing a strengths-based community-asset map16 to be invaluable―highlighting museums, historical landmarks, businesses owned by active community supporters and students’ family members, community-development organizations, key stakeholders, and more. I recommend that teachers make friends with the local librarian, who can also be a good resource. He or she will either be able to locate primary or secondary resources within your topic/content area or connect you to people who can.

Teachers should keep in mind that the more often students see the faces of people from many different cultures at the front of their classroom, the more they will be able to see reflections of themselves within the educational culture. When given the choice, I (CB) have purposefully sought substitute teachers, teacher’s assistants, and guest speakers whose cultures and experiences were similar to those of my students. These people provided learning opportunities for my students that I would never have been able to provide.

Tip 7. Commit to using a variety of processes for learning.

Along with a setting and curriculum that meet the needs of a diverse classroom, the methods and strategies used to engage students in the process of learning are equally influenced by culture. Students’ cultures shape the way they interact with one another, teachers, and the learning material. And although no student can be completely defined by his or her culture, it is wise for teachers to familiarize themselves with some of the ways that culture manifests itself in the classroom and influences how students think about the learning process and how they actually learn.

The cultural values of individualism and collectivism shape how students involve themselves in the learning process. While individualist cultures emphasize individual success and personal choice, collectivist cultures focus on relationships and the advancement of the group.17 A teacher may find that students who come from more collectivist cultures (which make up the majority of the world’s populations) tend to listen rather than speak, thrive during cooperative tasks, and express interest in social skills development as part of their education. Those from more individualistic cultures tend to be galvanized by personal achievement, dialogue, and competition. Since teachers will have students from collectivist and individualistic cultures, both types of learning tasks must be incorporated into classroom instruction to accommodate the needs of all students.

I (CB) learned that students from collectivist cultures often responded to my questions with silence. Using an active pause (“wait time”)18 gives students time to think before responding, a behavior that is highly valued within their culture. Putting them in small groups or calling on them by name also makes it more likely they will be comfortable participating in classroom discussions.19

Tip 8. Engage students in critical thinking and dialogue to build cultural capital.

When they recognize that the formal curriculum can be a source of bias, educators are better able to critically assess the materials they are teaching. But more than that, including students in this analysis is a powerful learning tactic. In her landmark study, Gloria Ladson-Billings20 found that excellent teachers of African American students engaged them in a review of their textbooks. In this way, although the required curricula are used, students get to critically engage with them in ways that are empowering. This approach works well for all students, giving them the opportunity to study a topic from multiple points of view. They also get to think critically about the strengths and weaknesses of an argument while building and refining their own point of view.

Another way to involve students in culturally relevant learning experiences is to assist them in developing critical consciousness about their attitudes toward learning particular information. Many of my (CG) students at the second-chance workforce development academy balked at learning Standard English. It was, of course, necessary for their academic success; however, it felt fake or forced to them at best. I needed a different tactic. By knowing about the settings within which they functioned, I could engage students in critical-thinking activities related to their circles of interest. We drew large circles on the whiteboard for each student, and usually identified at least two domains in which they were already successful. They knew how to stay safe on the street, how to navigate conversations with family by using dialect or another language to communicate in different social settings, and so on. The circle they did not yet know how to access fully was the work world. So, we built on their understanding of code switching21—a social-theory term for adapting forms of communication to meet the environment—and helped them learn Standard English in order to reach their employment goals.

Tip 9. Redefine the roles of teacher and student.

Rooted in the dialogic teaching approach (an approach that relies on conversation to help stimulate and extend students’ thinking) is the idea that students should begin to “take on roles and responsibilities that have been traditionally reserved for the teachers.22 This requires that teachers value the knowledge students bring to the classroom and consider themselves to be learners along with their students.

For me (CB), repositioning myself into the role of teacher-learner, not just teacher, was challenging. As I eased into the role, I experienced discomfort. I quite liked being the most knowledgeable person in the classroom. But the rewards I gained from letting go of my expert status at key moments were worthwhile. Instead of correcting what at first glance looked like errors, I observed, asked questions, and learned.

For example, I noticed one student in math class counting by threes (rather than, say, twos or fives or tens), and I felt confused about why she was not using an easier skip counting strategy. “I notice that you’re counting by threes. Tell me more about what you’re doing here,” I said. The student next to her joined the conversation. “She was in 3rd grade in Honduras, and when we’re in 3rd grade [in Honduras], we’re learning our times tables. That’s how we practice them.” The discussion continued for several minutes, as students shared the many ways they were taught math in their home countries. Making space for this important dialogue gifted me with a clearer picture of the content, teaching styles, and strategies with which my students were already familiar, and gave me ideas for incorporating their previous experiences into later lessons.

Redefining the role of teacher and student has challenged both of us (CB and CG). Initially, I (CG) found it easier to hand off the teacher role to another expert from the community than to embrace what I felt was a “messier” student-as-teacher way of learning. However, the reward has been worth it! In an interdisciplinary America’s Westward Expansion unit (one that was remade to correct the mistakes acknowledged earlier), I joined both Navajo and white students as we grappled together with issues relating to expansion, removal, justice, God, and religion. One of the most moving and humbling moments in my teaching career came when one of my Navajo 5th-grade students made a decision toward reconciliation. He had been struggling with deep anger as we learned more about the ill treatment of the Navajo people during the “Long Walk” from their land in what is now Arizona to eastern New Mexico and their stay at Fort Sumner,23 and yet he had also been journeying with us as a class toward justice and reconciliation. While on a field trip to Fort Sumner, he looked at us solemnly and said, “I place this arrowhead on this memorial because arrowheads are weapons, and I’m not going to fight white people anymore.” I’m still in touch with that particular student. I can testify that he was serious about his commitment. He continues to work toward justice for Navajo people, and now as a young adult, his work is not driven by hatred.

Summary

The journey toward culturally relevant teaching may require foundational shifts in the way we view ourselves and our students, and may require us to adopt different strategies in order to achieve maximum impact on student success. It is not enough to simply say that we are all human and all loved equally by God; we must be intentional in our planning as we put these words into action. CRT does not mean engaging in celebratory multiculturalism24 (emphasis on celebrating food, holidays, or traditions) or incorporating race into the curriculum while continuing to teach from the same viewpoint and using the same strategies. It requires sustainable and rigorous reflection on our ways of thinking and being. We must help our students push back against dominant, often negative, narratives about people regardless of their background by encouraging them to develop resilience. In every country there is a dominant culture that interacts with a minority culture, and sadly, these interactions are not always positive. Our students need to learn to live in multiple environments—their home community, the dominant community, and an increasingly blended, diverse world. As you explore what CRT will look like in your classroom, we hope you will benefit from learning from our experiences—not only our successes but also our “teachable moments.”

This article has been peer reviewed.

Recommended citation:

Charity Garcia and Charissa Boyd, “Engaging in Culturally Relevant Teaching: Lessons From the Field,” Journal of Adventist Education 81:3 (July–September, 2019). Available at https://www.journalofadventisteducation.org/en/2019.81.3.4.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

- The Brown Center for Education Policy, “Teacher Diversity in America” (2017-2019): https://www.brookings.edu/series/teacher-diversity-in-america/; Huanshu Yuan, “Multicultural Teacher Education in China: Preparing Culturally Responsive Teachers in a Multiethnic and Multicultural Country,” US-China Education Review B 7:2 (February 2017): 85-97. doi:10.17265/2161-6248/2017.02.003; Hajar Akl, “Diversity Gap: ‘There Are No Muslim, Asian or Indian Teachers,’” The Irish Times (September 2017): https://www.irishtimes.com/news/education/diversity-gap-there-are-no-muslim-asian-or-indian-teachers-1.3219678; Jenny Rosén and Åsa Wedén, “Same but Different: Negotiating Diversity in Swedish Pre-school Teacher Training,” Journal of Multicultural Discourses 13:1 (February 2018): 52-68.

- Ellen G. White, True Education (Nampa, Idaho: Pacific Press, 2000), 12.

- Gloria Ladson-Billings, The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teaching for African-American Students (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1994), 17, 18.

- __________, “But That’s Just Good Teaching! The Case for Culturally Relevant Pedagogy,” Theory Into Practice 34:3 (Summer 1995): 159-165.

- National Council of Teachers of English Position Statement, “Supporting Linguistically and Culturally Diverse Learners in English Education” (July 31, 2005): http://www2.ncte.org/statement/diverselearnersinee/; Lourdes Díaz Soto, Jocelynn L. Smrekar, and Deanna L. Nekcovei, “Preserving Home Languages and Cultures in the Classroom: Challenges and Opportunities,” Directions in Language and Education (Spring 1999): https://ncela.ed.gov/files/rcd/BE021107/Preserving_Home_Languages.pdf.

- Lee Jussim and Kent D. Harber, “Teacher Expectations and Self-Fulfilling Prophecies: Knowns and Unknowns, Resolved and Unresolved Controversies,” Personality and Social Psychology Review 9:2 (May 2005): 131-155.

- White, True Education, 12.

- Henry Levin et al., “The Public Returns to Public Educational Investments in African- American Males,” Economics of Educational Review 26:6 (December 2007): 699-708; James L. Moore III, Malik S. Henfield, and Delila Owens, “African American Males in Special Education: Their Attitudes and Perceptions Toward High School Counselors and School Counseling Services,” American Behavioral Scientist 51:7 (March 2008): 907-927; Pedro Noguera, “The Trouble With Black Boys: The Role and Influence of Environmental and Cultural Factors on Academic Performance of African American Males,” Urban Education 38:4 (July 2003): 431-459.

- Gilman Whiting, “Gifted Black Males: Understanding and Decreasing Barriers to Achievement and Identity,” Roeper Review 31 (2009): 224-233.

- Elizabeth Coelho, Language and Learning in Multilingual Classrooms: A Practical Approach (Bristol, U.K.: Multilingual Matters, 2012).

- Ibid.; Diane Rodríguez, Angela Carrasquillo, and Kyung Soon Lee, The Bilingual Advantage: Promoting Academic Development, Biliteracy, and Native Language in the Classroom (New York: Teachers College Press, 2014).

- Coelho, Language and Learning in Multicultural Classrooms; Jim Cummins, “A Proposal for Action: Strategies for Recognizing Heritage Language Competence as a Learning Resource Within the Mainstream Classroom,” The Modern Language Journal 89:4 (Winter 2005): 585-592.

- Ibid.; Center for Applied Linguistics, “Bilingual and Dual Language Education” (2019): http://www.cal.org/areas-of-impact/english-learners/bilingual-and-dual-language-education; Jennifer L. Steele et al., “Effects of Dual-Language Immersion Programs on Student Achievement: Evidence From Lottery Data,” American Educational Research Journal 54:1 (April 2017): 282S-306S. doi:10.3102/0002831216634463.

- Elise Trumbull et al., Bridging Cultures Between Home and School (Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2001).

- Linda Baird and Marlon Peterson, “Introduction to Community Asset Mapping” (June 2011): https://www.courtinnovation.org/sites/default/files/documents/asset_mapping.pdf

- Ibid.

- Professional Learning Board, “How Can the ‘Pause Procedure’ Be Used to Enhance Learning?” (n.d.): https://k12teacherstaffdevelopment.com/tlb/how-can-the-pause-procedure-be-used-to-enhance-learning/.

- Lane Kelley, Elaine K. Bailey, and William David Brice, “Teaching Methods: Etic or Emic,” Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning 28 (2001): 123-126.

- Ibid.

- Ladson-Billings, “But That’s Just Good Teaching! The Case for Culturally Relevant Pedagogy,” 159-165.

- Jennifer Gonzalez, “Know Your Terms: Code Switching” (June 2014): https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/code-switching/.

- Alina Reznitskaya and Ian A. G. Wilkenson, “Positively Transforming Classroom Practice Through Dialogic Teaching.” In Positive Psychology in Practice: Promoting Human Flourishing in Work, Health, Education, and Everyday Life, 2nd ed., Stephen Joseph, ed. (Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons, 2015), 279-296.

- For more information about the Long Walk see Jennifer Denetdale’s The Long Walk: The Forced Navajo Exile (New York: Chelsea House Publications, 2007); Dennis Zotigh, “The Treaty That Reversed a Removal—the Navajo Treaty of 1868” (February 2018): https://www.smithsonianmag.com/blogs/national-museum-american-indian/2018/02/22/treaty-that-reversed-a-removal-navajo-treaty-1868-goes-on-view/.

- Celebratory multiculturalism is defined as seeking to understand and affirm aspects of culture that can influence a learner’s performance in school or shed light on his or her personal experiences, such as celebrating food and holidays, beliefs, traditions, values, or learning about the types of advocacy needed or practiced within the specific community. This type of multiculturalism is often seen in governments, education (schools), or businesses in the form of policy and celebratory events. For more information see: Multicultural Education Vocabulary, https://quizlet.com/22156199/multicultural-education-vocab-flash-cards/.