Millennial students1 have different characteristics than previous generations,2 and those coming to Adventist institutions of higher learning are compelling the institutions to change. Based on conversations with a cross-section of Seventh-day Adventist students attending the denomination’s colleges and universities, the authors learned that these millennials are looking to be engaged, and they want our Adventist biblical worldview to be prevalent throughout all their courses. When they graduate, Adventist millennials want to be ready to meet the world head on, with their biblical worldview developed. They, like other millennials, want to come away with an understanding of how the Scriptures apply to their vocation and calling.3

Establishing a Biblical Worldview

Establishing a biblical worldview in all courses is of utmost importance in Adventist institutions of higher education, especially when everyone has access to the wealth of information found on the Internet today. For example, many top-tier universities offer Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCS) for free,4 allowing individuals to earn certificates of mastery and completion that can be used to document personal and professional growth. Courses taken at Adventist colleges and universities, whether online or in a physical classroom, need to be different from what students can find online. Courses should be designed to provide students with a uniquely Adventist perspective, structured on a biblical foundation.

Joshua gave the Israelites a clear choice similar to the choice professors are given: “Choose you this day whom ye will serve; whether the gods which your fathers served that were on the other side of the flood” (i.e., a traditional approach, teaching the way we were taught), “or the gods of the Amorites, in whose land ye dwell:” (i.e., a contemporary approach, teaching the way things are taught in other institutions) “but as for me and my house” (classroom), “we will serve the Lord”5 (i.e., follow the divine plan for education built on the foundation of Scripture, committed to service, with a view of eternity).

The importance of this choice is highlighted in the book Total Truth. Author Nancy Pearcey warns professors about what happens when one hasn’t developed a biblical approach for delivering the course content:

“The danger is that if Christians don’t consciously develop a Biblical approach to the (academic) subject, then we will unconsciously absorb some other philosophical approach. A set of ideas for interpreting the world is like a philosophical toolbox, stuffed with terms and concepts. If Christians do not develop their own tools of analysis, then when some issue comes up that they want to understand, they’ll reach over and borrow someone else’s tools—whatever concepts are generally accepted in their professional field or in the culture at large. . . . ‘The tools shape the user.’”6

An extensive search of the literature provided no course design model with a biblical foundation and an Adventist perspective for use within Adventist institutions of higher education. Therefore, the authors chose to develop a model, based on respected research-based techniques, beginning with a clearly identified biblical concept as its foundation. The next section describes seven steps for designing a course using the Biblical Foundation Course Design Model created by the authors.

Steps to the Biblical Foundation Course Design Model

Step 1: Create a Course Concept Map. The professor should begin the process by “beginning with the end in mind”7 through specific reflection on the following questions: “What is the essential overarching concept of my course?” “How is this concept a truth about God?” and “What Biblical Examples (BEs) of this concept can be shared meaningfully throughout this course?” The answers to these questions are used to begin the development of the Biblical Foundation Course Concept Map (BFCCM), a visual representation of the course’s biblical foundation and its connection to course content. The map streamlines the professor’s thinking and outlines the biblical course concept and its connection to BEs, the academic knowledge and processes of the course, along with assessments that will be used to measure the student’s grasp of the content. Because the BFCCM is a visual representation of all essential elements of the course design, it becomes an important part of the course syllabus.

| Biblical Course Concepts Identified by Professors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Abundance

Acceptance Accountability Adaptation Adjustment Alignment Ambition Appreciation Balance Beauty Belonging Brotherhood Caring Change Character Choice Circle of Life Commitment Communication Compassion Connection Cooperation Coping Courage Creativity Culture |

Death/Dying

Democracy Dependency Design Desire Discovery Diversity Emotions Empowerment Environments Equality Eternity Ethics Excellence Experience Fairness Faith Family Feelings Forgiveness Free Will Freedom Friendship Fulfillment Grace Gratitude |

Growth

Harmony Heroism Hierarchy Honor Hope Humor Identity Individuality Intentionality Interaction Interdependence Justice Knowledge Leadership Liberty Living Love Loyalty Morals Nationalism Nature Order Organization Overcoming Patterns |

Peace

Perspective Power Reality Rebellion Rebirth Reconstruction Redemption Reflection Relationships Renewal Restoration Rhythm Self-Awareness Self-Worth Strength Systems Tradition Transformation Trust Truth Unity Values Will |

To start creating the Biblical Foundation Course Concept Map, the professor identifies two to three biblical concepts that could represent the essence of the course. See Table 1 for a partial list of biblical concepts that were collected by professors. Next, the professor should spend time in Bible study, prayer, and reflection on the identified biblical concepts, asking God to help determine which one biblical concept will best represent the truth of God within the content knowledge of his or her course.

The professor continues the process by writing the defining sentence using the selected biblical course concept word and describing its connection to the course’s academic content in one sentence. For example, Linda Crumley, professor of COMM 397: Communication Research at Southern Adventist University in Collegedale, Tennessee,8 identified “Discovery” as the biblical course concept because she identified the biblical basis for her course as follows: “God reveals many things to us.” Dr. Crumley then wrote her defining sentence: “Through Discovery we seek to discover what God wants to reveal,” from Deuteronomy 29:29.

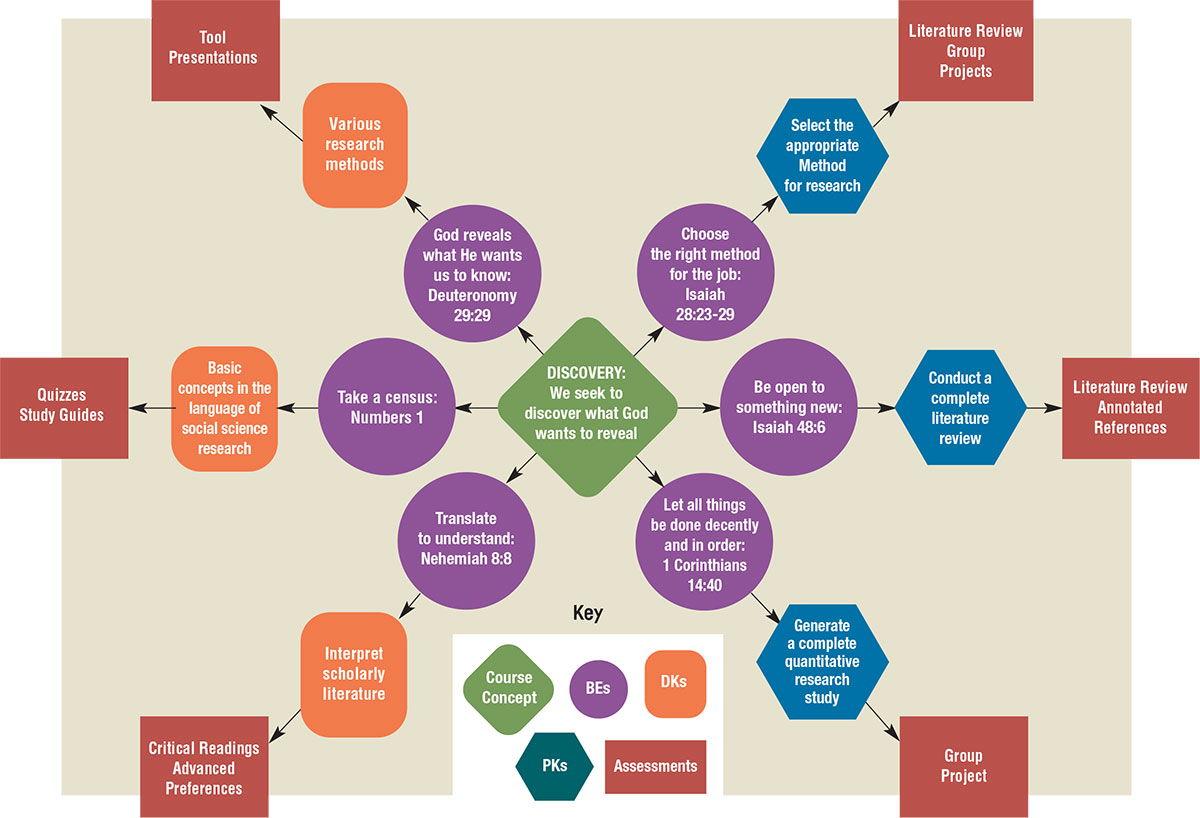

She placed the biblical course concept and the defining sentence in a green diamond shape in the center of the Biblical Foundation Course Concept Map. Figure 1 shows the beginning of the Course Concept Map for COMM 397: Communication Research.

Figure 1. — Biblical Course Concepts and Defining Sentence for COMM 397: Communication Research

Next, the professor identifies Biblical Examples (BEs), which include biblical teachings and specific Bible stories, with the reference texts, that relate to the biblical course concept and defining sentence.

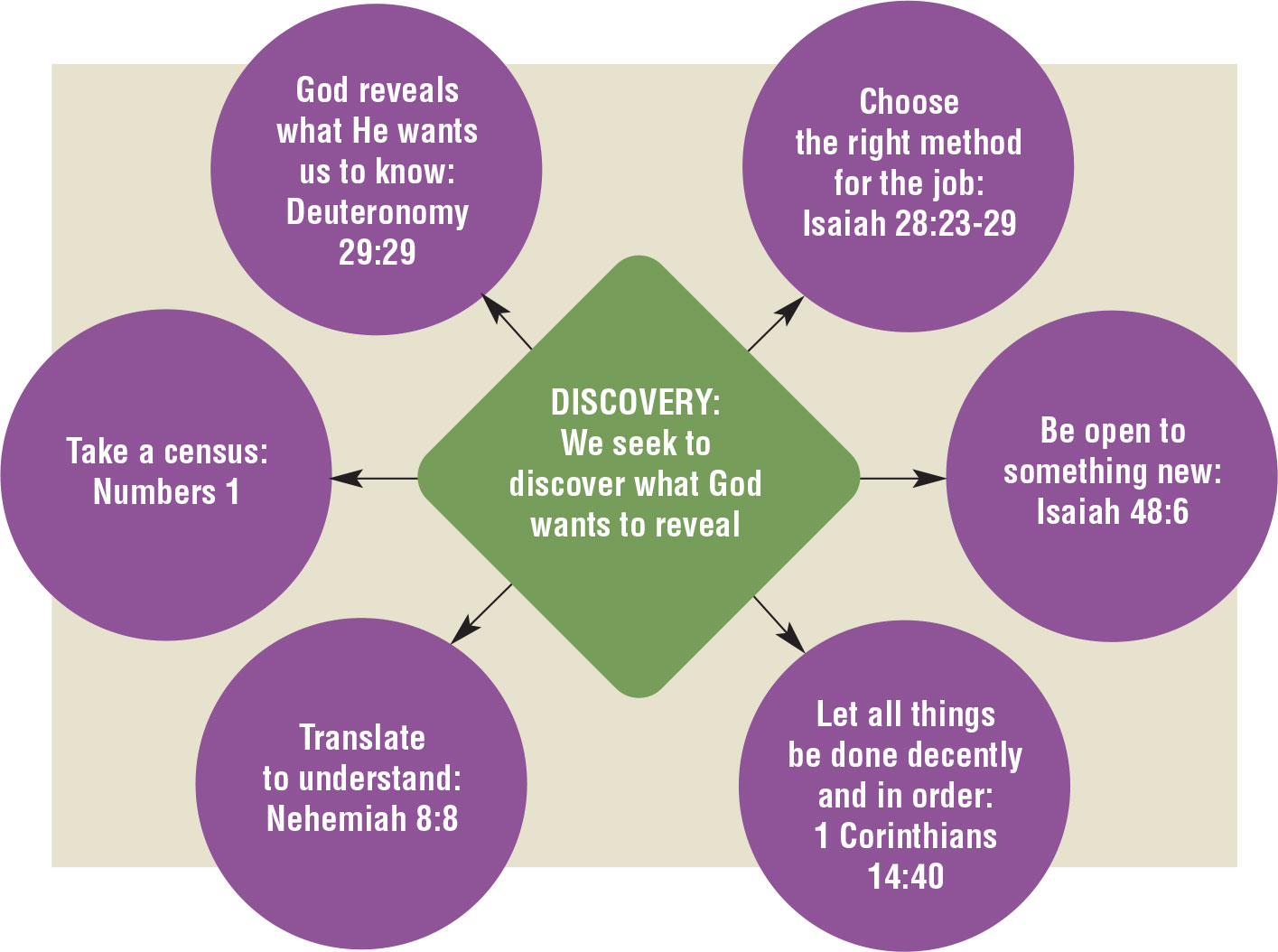

Dr. Crumley identified six BEs for her course:

- Deuteronomy 29:29—God reveals what He wants us to know.

- Isaiah 28:23-29—Choose the right method for the job.

- Isaiah 48:6—Be open to something new.

- 1 Corinthians 14:40—Let all things be done decently and in order.

- Nehemiah 8:8—Translate to understand.

- Numbers 1—Take a census (a procedural format).

The professor placed each of the BEs in a separate purple circle and connected, with arrows, the biblical course concept to each of the BEs on the Course Concept Map. Figure 2 shows the BEs added to the Biblical Foundation Course Concept Map for COMM 397. (Note that, should this course be taught by other professors, they may see the purpose of the course differently and find a different biblical concept and/or additional or different BEs.)

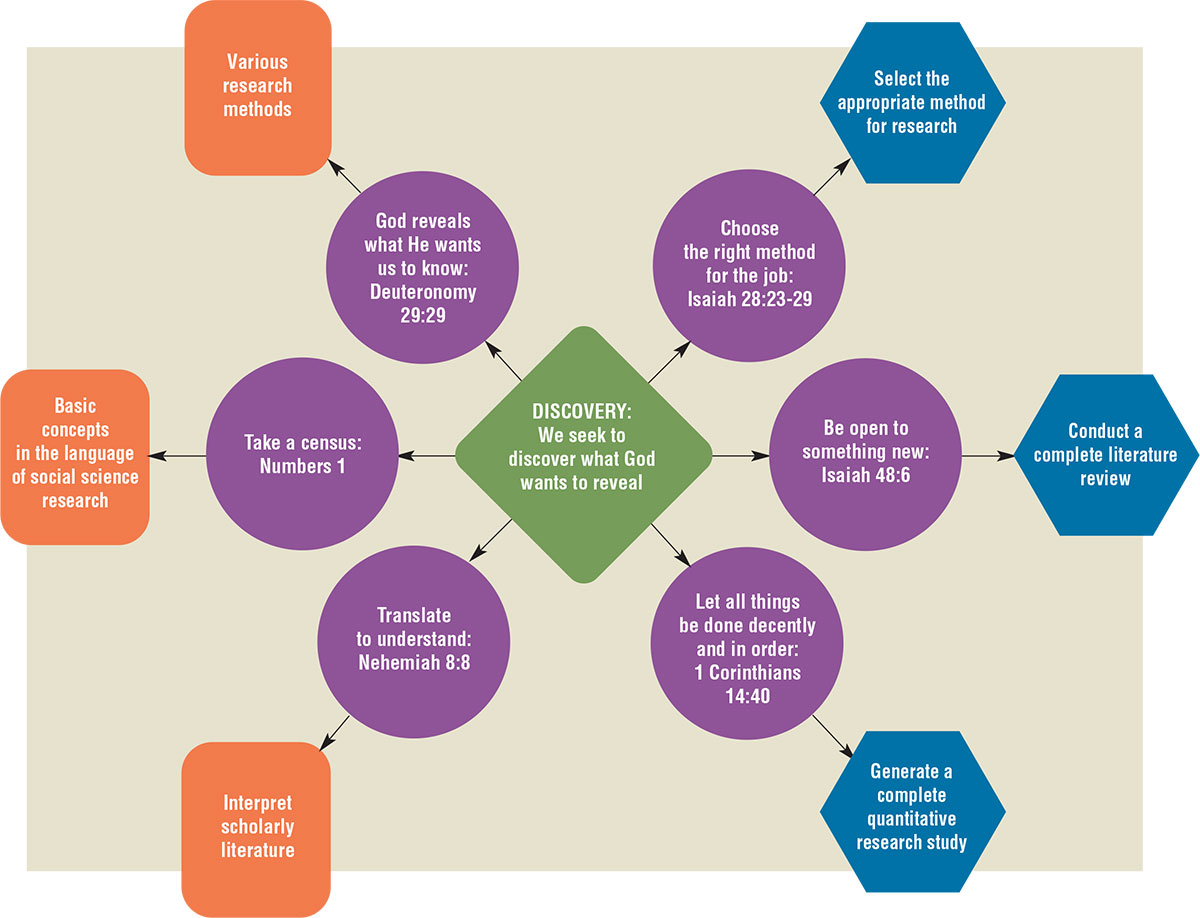

The Biblical Foundation Course Design Model, like Stage 1 of McTighe and Wiggins’ popular Understanding by Design Model,9 emphasizes the identification of the desired end results for the course content knowledge. The professor does this by determining what declarative (DK) and procedural knowledge (PK) students need to know to demonstrate understanding of the course content. These DKs and PKs will answer the question, “Five years after taking this course, what should students know and be able to do?” Some professors will add state of attitudes and values, in addition to the DKs and PKs. Dr. Crumley identified three DK statements and three PK statements for her course. On her Biblical Foundation Course Concept Map, she placed each DK in an orange rectangle and each PK in a blue hexagon and added them to the map. Most professors do not have an identical number of DKs and PKs. However, the professor should limit the total number of combined DKs and PKs to no more than eight well-structured statements to ensure clear alignment to the learning outcomes.

The professor now reviews the BEs already identified and determines which one(s) connect best with each DK or PK. The BEs are usually placed on the Biblical Foundation Course Concept Map close to the DK or PK where they best connect, and an arrow is drawn connecting them. Figure 3 shows the Biblical Foundation Course Concept Map with the DKs and PKs added for COMM 397.

Finally, to complete the BFCCM, the professor determines what kinds of assessments best measure student understanding of each DK and PK. For millennials, real-world activities or projects should be used whenever possible. The professor places the assessments in red rectangles and connects each to the appropriate DK or PK.

Figure 2. — Biblical Examples Tied to Biblical Course Concept for COMM 397: Communication Research

In COMM 397, Dr. Crumley chose to use Tool Presentations such as Prezi or Keynote for iCloud, Literature Reviews, Study Guides, Annotated References, Choral Readings, and a Group Project, along with tests, as the assessments for her course. She did not rely solely on quizzes and tests, which are low-level assessments, and should not be the only type of assessment used. (It is important to note that in Step 5 of the Biblical Foundation Course Design Model, the professor will write an expanded Assessment Plan [AP] that will incorporate more information for the assessment activities identified here.)

The completed Biblical Foundation Course Concept Map for COMM 397 (see next page) shows the biblical course concept and the defining sentence connected to the BEs, the BEs connected to the DKs and PKs, and the DKs and PKs connected to their corresponding assessments.

Figure 3. — DKs and PKs Added to Course Concept Map for COMM 397: Communication Research

View Larger

View Larger

Step 2: Write the Learning Outcomes (LOs). LOs describe in sentence form what students will be able to demonstrate in terms of knowledge and procedures upon finishing the course. The LOs build on the DKs and PKs identified in the Concept Map of Step One and are designed to intentionally show the progression of the learning process to move students toward higher-order thinking as represented by the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy.10 The LOs will be recorded in the course syllabus so students understand what will be expected of them as they complete the course.

Figure 4. — Biblical Foundation Course Concept Map for COMM 397: Communication Research

View Larger

View Larger

The professor should write one Learning Objective for each DK and PK. When writing the LOs, the professor must remember to focus on student learning and state the LOs in clear, measurable, and observable terms. Vague words such as understand, know, and become familiar with are difficult to measure and should be avoided. Instead, instructors should choose action verbs from the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy, such as perform, identify, describe, explain, and demonstrate.11 Foundational courses, or General Education courses, will use more verbs from the lower levels of the taxonomy—remember, understand, apply—while upper-division and graduate courses will draw more from the higher levels—analyze, evaluate, create.

Table 2 shows the LOs for COMM 397. Remember, there is a one-to-one correlation between each outcome and a DK or PK; and each LO should begin with an active verb from the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy. LOs should be listed after the sentence stem, “Upon successful completion of this course, the student will be able to . . . .” The taxonomy category is listed in parenthesis after the LO.

| Table 2. Learning Outcomes for COMM 397: Communication Research |

|---|

|

Upon successful completion of this course, the student will be able to:

|

Step 3: Select Active Teaching and Learning Activities. Active Teaching and Learning Activities (T/LAs) feature a wide range of strategies but with the commonality of “involving students in doing things and thinking about the things they are doing,” according to Bonwell and Eison’s research.12 Active T/LAs should be identified and used to engage students—a specific need of millennial students.13 Professors must identify the significant DKs and PKs of the content and develop activities that present opportunities for students to apply the thinking skills used by professionals in the discipline. These active teaching and learning activities replace lecturing for the entire class period; and many research studies indicate they lead to greater academic achievement among all adult learners, including millennials.

The major characteristics associated with active learning, as defined by researchers, include the following: increased student motivation, especially for adult learners; reciprocal feedback between student and professor; and student involvement in higher-order thinking (analyzing, evaluating, and creating).The professor should plan to introduce each Learning Objective by incorporating several active teaching and learning techniques in his or her daily plans.

Active learning techniques range from simple (i.e. periodic pauses, minute paper,14 or think-pair-share15) to complex (i.e., simulation, problem-based learning, and/or service learning), which involve more preparation and classroom time. Detailed strategies and more information on the benefits of active teaching and learning techniques can be found by visiting the following links:

- http://cei.umn.edu/support-services/making-active-learning-work16

- http://www.fctl.ucf.edu/TeachingAndLearningResources/CourseDesign/Assessment/content/101_Tips.pdf.17

Active T/LAs release both the professor and the student from covering every page in a textbook and move the textbook to its rightful place in the course—a resource. These activities also allow professors time to bring in the biblical connections and Adventist beliefs identified in the first step of this Course Design Model. Students need to see the connections between the biblical course concept, BEs, and the DKs and PKs and the class activities and assignments.

Step 4: Plan for Feedback. Designing a Feedback Plan (FP) is the fourth step in the Biblical Foundation Course Design Model, which should become part of the course syllabus. The FP has two parts: first, it outlines how the professor will ask for feedback from the students; and second, how the professor will give feedback to the students. Without a Feedback Plan, most assignments are often seen as busy work by students. The absence of prompt, useful feedback reduces interest in learning. When professors provide prompt feedback to the students, followed by a discussion of incorrect responses, they are implementing one of the most powerful predictors of positive student outcomes. Research on the study of the human brain indicates that humans are biologically wired to seek and use feedback.18

The professor should provide student feedback within 24 to 48 hours19 to intentionally “close the assessment loop” for most assignments. Ideally, this closure allows students to utilize the professor’s input to improve their learning in subsequent class activities and assignments.20 For major assignments that require more time, professors should state the expected return date in the syllabus and remind the students of this when the assignment is collected.

Feedback from students is often overlooked by professors. One quick technique, The Minute Paper,21 can be used by professors to obtain student feedback. The professor asks students to write in class for one minute and answer one question similar to this: “What was the most important thing you learned during this class?” “What important question remains unanswered?” Or “Give an example that relates to the topic of the day.”

Step 5: Plan for Assessment. The Assessment Plan (AP) itself should be approached in a way that reflects a biblical worldview. Evaluation has a spiritual significance, as we are reminded in Deuteronomy, “The LORD your God is testing you.”22 The primary purpose of evaluation is for students to know how to discard error and retain truth, “But test them all; hold on to what is good.”23 Professors, too, must keep in mind that they themselves will be judged by the manner in which they evaluate, “For in the same way you judge others, you will be judged, and with the measure you use, it will be measured to you.”24

In order for professors to make assessment a valuable learning tool, learners need to know, upfront, what to expect and when to expect it. They also desire options; variety in assessment options that target different learning styles is appreciated by millennial learners because it presents a more accurate representation of the learning taking place. Therefore, a formal AP should be written and placed in the syllabus outlining what types of assessment, including formative and summative, will be part of the course; when will the assessments take place; and how the assessments will be evaluated. The AP should also include rubrics or checklists for all major assignments and the grading scale that will be used in the course.

Step 6: Check for Alignment. An important element of the Biblical Foundation Course Design Model is alignment. All components of the model should be checked to make sure they align with one another. The professor should remember the following:

- The course’s biblical foundation of faith and learning should be represented by the biblical course concept and defining sentence, which should be naturally connected through the biblical examples (BEs) to a declarative knowledge (DK) and/or procedural knowledge (PK).

- There should be at least one assignment, active teaching and learning activities (T/LA), and assessment for every learning outcome (LO).

- Critical LOs need to be revisited often throughout the semester and may need several assignments, active T/LAs, and assessments.

- Every T/LA should align to a DK or PK; and every DK and PK should align to a LO; and every LO should be assessed.

Step 7: Prepare a Detailed Syllabus. Finally, in culmination of the newly designed course, the professor produces a detailed syllabus that reflects both the requirements of the college or university and keeps in mind the preferences of all students.25 Professors should do the following:

- Write a paragraph describing the biblical foundation connection to the course content knowledge.

- Include the newly designed elements illustrating the course’s biblical foundation, such as the Biblical Foundation Course Concept Map, LOs, and the FP and AP, which includes assignment options and the course calendar.

- List the ways students should contact them, if needed, outside of class time including regular and electronic “office hours.”

- Give hours and contact information for additional help possibilities such as the IT/IS or Learning Management System Help Desk(s), library resources, research and writing center help, and/or tutors and lab assistants, etc.

- Provide copies of required policies from the institution such as those relating to (1) students with disabilities, and (2) academic honesty (plagiarism).

- Make sure directions for completing all the assignments listed in the course calendar are described in detail, and rubrics or checklists are provided for major assignments.

For additional information on each step, see: http://www. southern.edu/administration/cte/Docs/Biblical_Foundations_Course_Design_Steps.pdf.

Conclusion

Generational differences will continue throughout time. Therefore, higher education must also change to meet the specific needs of each group enrolled in the institution. In developing the Biblical Foundation Course Design Model, the authors felt convinced that all professors would be able to teach from a uniquely Adventist biblical foundation, as well as meet the distinctive needs of the millennial generation. Under this model, every course taught at a Seventh-day Adventist institution of higher education will differ significantly from similar courses taught at secular or other Christian institutions. Furthermore, when this model is followed, professors will be better prepared to lead students into a deeper understanding of a faith-based biblical worldview and educate students to think biblically rather than humanistically. The final outcome should produce students who are capable of incorporating the Adventist biblical worldview into real-world occupational settings, and who are better able to make a difference for Him through their calling and vocation.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Recommended citation:

Cynthia M. Gettys and Elaine D. Plemons, “A Biblical Foundation Course Design Model That Works: Teaching Millennials in Higher Education,” Journal of Adventist Education 79:1 (October–December 2016). Available at https://www.journalofadventisteducation.org/en/2017.1.5.

Notes and References

- Neil Howe and William Strauss, authors of the best-seller Millennials Rising: The Next Generation (New York: Vintage Books, 2000), provided the first comprehensive look at this specific generation and defined millennials as those born between 1982 and 2004. This group includes the wide range of students (traditional and non-traditional) enrolled in higher education in face-to-face and online classrooms globally.

- Paula Gleason, “Meeting the Needs of Millennial Students,” In Touch Newsletter 16:1 (Winter 2008) Student Services, California State University, Long Beach: http://web.csulb.edu/divisions/students2/intouch/archives/2007-08/vol16_no1/01.htm. Unless otherwise indicated, all Websites in the endnotes were accessed in July 2016.

- Rick Ostrander Interview with David Kinnaman and Gabe Lyons, “Developing Good Faith,” Advance (Washington, D.C.: Counsel for Christian Colleges and Universities, Spring 2016): 54, 55: https://issuu.com/cccu/docs/16_springadvance_web/55.

- Open Culture, “MOOCs From Great Universities (Many With Certificates)” (2016): http://www.openculture.com/free_certificate_courses.

- Joshua 24:15, King James Version.

- Nancy Pearcey, Total Truth: Liberating Christianity From Its Cultural Captivity (Wheaton, Ill.: Crossway Books, 2005), 44.

- Stephen Covey, Seven Habits of Highly Effective People (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1989), 95-144.

- Name and course materials used with permission.

- Jay McTighe and Grant Wiggins, Understanding by Design Guide to Creating High-quality Units (Alexandria, Va.: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2011).

- Loren Anderson, A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Complete Edition (New York: Worth Publishers, 2010).

- Ibid.

- Charles Bonwell and James Eison, “Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom,” in ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 1 (Washington, D.C.: George Washington University, 1991), 19.

- Jeff Nevid, “Teaching the Millennials,” Observer 24:5 (May/June 2011), Association for Psychological Sciences: http://www.psychological science.org/index.php/publications/observer/2011/may-june-11/teaching-the-millennials.html. Accessed July 26, 2016.

- See “Minute Paper,” in Office of Graduate Studies, University of Nebraska for a description of how to use: http://www.unl.edu/gradstudies/current/teaching/minute. The Minute Paper is a classroom assessment technique made popular by Thomas A. Angelo and K. Patricia Cross in their well-known resource Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: Josey-Bass, 1993).

- See Think-Pair-Share: http://archive.wceruw.org/cl1/cl/doingcl/thinkps.htm and http://serc.carleton.edu/introgeo/interactive/tpshare.html for more about this cooperative learning strategy.

- “What Is Active Learning?” in University of Minnesota, Center for Teaching and Learning: http://www1.umn.edu/ohr/teach-learn/tutorials/active/what/index.html.

- “Interactive Techniques” In Teaching and Learning Resources, University of Central Florida, Karen L. Smith Faculty Center for Teaching & Learning: http://www.fctl.ucf.edu/TeachingAndLearnngResources/CourseDesign/Assessment/content/101_Tips.pdf.

- James Zull, From Brain to Mind (Sterling, Va.: Stylus Publishing, 2011).

- John McCarthy, “Timely Feedback: Now or Never,” Edutopia (January 2016): http://www.edutopia.org/blog/timely-feedback-now-or-never-john-mccarthy; Grant Wiggins, “Seven Keys to Effective Feedback,” Educational Leadership 70:1 (September 2012):10-16: http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/sept12/vol70/num01/Seven-Keys-to-Effective-Feedback.aspx.

- James Nichols and Karen Nichols, A Road Map for Improvement of Student Learning and Support Services Through Assessment (Flemington, N.J.: Agathon Press, 2005).

- “Minute Paper,” in Office of Graduate Studies, University of Nebraska.

22. Deuteronomy 13:3. New International Version (NIV). Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV ® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. - 1 Thessalonians 5:21, NIV.

- Matthew 7:2, NIV.

- Students enrolled in Adventist colleges and universities worldwide represent a global community. Several studies have sought to discover whether Millennials from different parts of the world share the same needs and concerns. The 2015 IRIS Millennials Survey (translated into more than 10 different languages) interviewed 23,000 students from 23 different countries: http://irismillennials.com/articles/2015-survey/; Universum Global conducted the first large-scale study of Millennials’ attitudes, actions, and how these varied worldwide. They surveyed 16,637 people in 43 countries across Asia, Africa, Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, and North America. Respondents were between the ages of 18 and 30 years old. The data are shared in a six-part report, “Understanding a Misunderstood Generation”: http://universumglobal.com/millennials/.